From architecture to fashion, our world is becoming increasingly monochromatic, but are retro aesthetics the path out?

Irrespective of your personal taste, the concept of colour dying is a stirringly despondent thought – one we’re all probably guilty of contributing to, one way or another.

In 2020, The Science Museum Group conducted an experiment, analysing thousands of objects designed over a 200 year period. With a perceptible “rise” in the use of grey, the results constituted a pretty damning indictment of the last few decades in terms of colour and design.

Since technicolour rocked the silver screen in 1939 with The Wizard of Oz, the next 40 years were a kaleidoscopic swirl of colour, with the peak, obviously, being the 70s, inspired in part by those vivid hallucinations that were mysteriously common at the time.

The question is then: how did we get here? Surprise, it’s not the one thing.

The first offers the most robust defence of this continual downtrend in colour amongst designers: minimalism, Bauhaus, brutalism and the holocaust.

Tel Aviv in Israel is a hell of a city. A well-designed and uniquely modern wonder-city sheltering a people and government who are the most and least deserving of it, respectively.

A reflection of Israel itself – it’s architecture was forged in the crucible of what Dostoevsky called the “bestial cruelty.” The largest concentration of brutalist and bauhaus buildings and installations on the planet, conceived of by a nearly-lost school of jewish artists, designers and architects – displaced and persecuted all.

The sharp angles, utility-based, inexpensive and, indeed largely colourless, design ethos of brutalism and bauhaus originated in post-war Britain and Weimar Germany respectively. Bauhaus in particular was singled out by the boarish philistines of the Nazi apparatus as a haven for communist and “culturally jewish” design. The school definitively closed the same year as Hitler’s ascendancy as chancellor.

The enormous success of brutalist and bauhaus artists spread beyond Israel’s borders and, for its part, changed the character of architecture and the visual arts for the next 40 years. Minimalism equally finds its root in the inexpensive and efficient design principles of the post-war period and has, in many ways, become one of the preeminent artistic philosophies of the last 60 years. From Apple to IKEA, the stirring imagery of minimalism, of bauhaus defined our homes and gadgets. The dawn of the personal computer, the touch-screen smartphone and the assemblable wardrobe, bed and table – riding a minimalist, white-black aesthetic.

This, if anything, is an enviable legacy. Though an incomplete one. Bauhaus, minimalism, brutalism and other aesthetics came to prominence in the post-war economic ruin of Europe. Their strength was only redoubled by the increasing demands for space and growth amidst the baby boom.

Charming, earthy and expensive marble and stone walls were replaced by monochromatic but cheap concrete. Hand-built wooden buildings and implements replaced by plastic and aluminium. Their efforts democratized art and cheapened housing and labour – but colour went by the wayside.

These were not the only art and design movements in the world however and, fortunately, the 50s, 60s and 70s knew it well. From the gaudy visual texture of the 50s diner to the weird but colourful pop art of the 60s, these eras were defined by a complex confluence of different tones and hues – all culminating in the positively psychedelic technicolour of the 70s. A near-permanent acid trip.

By the 2000s, it seemed that the era of lava lamps and the variety of fashion that epileptics still fear was putatively over. The era of sleek desk lamps and incrementally slimmer laptops – silver all – had dawned.

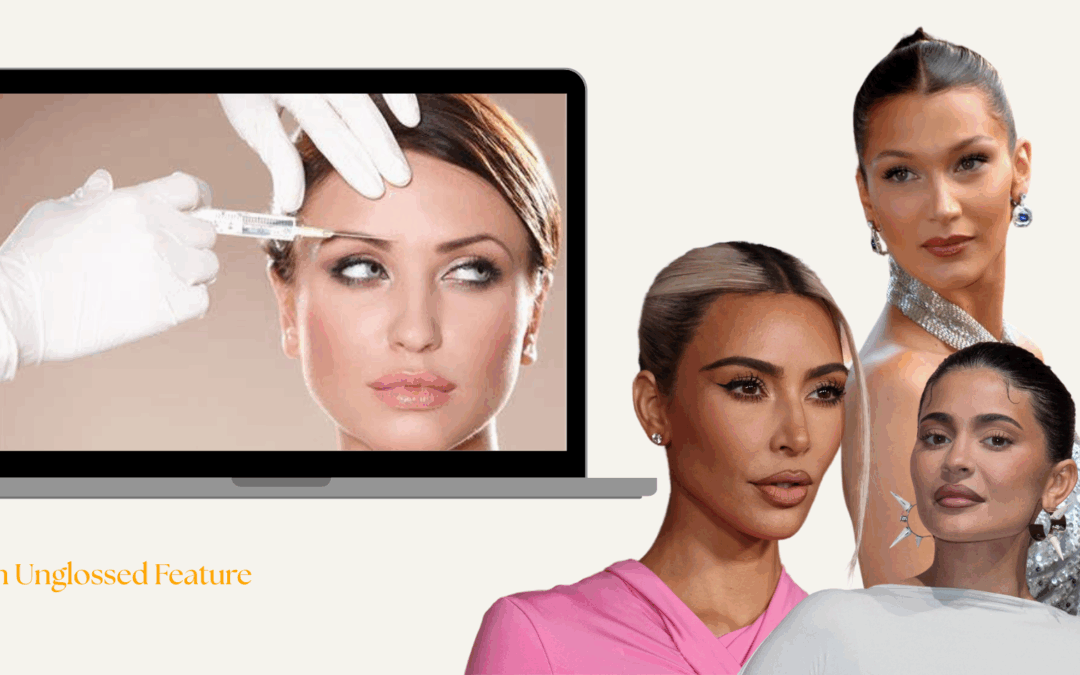

We still haven’t crawled out. “Clean girl” aesthetics, off-white wardrobe and loving, virgin-white, high-ponytailed, uptight, pristinely Nara Smith vibes permeate the air and envelop the senses.

Recently though, I’ve felt a new wind, and from the same place as colour previously found it’s cultural apex.

The retro craze isn’t the product of a marketing strategy, of grey men projecting colour from a boardroom for profit – but a somewhat depressing yet incidentally fortunate by-product of stagnation, economic and cultural.

Lets start with culture, and where you go when you don’t have the creativity to move forward. Spoilers: it’s backward.

From Stranger Things to Silk Sonic to even Usher’s rebirth, we’re experiencing an unprecedented era of nostalgia porn. Even in fashion, Y2K revisionism and the recession pop trend signify a resurgent desire for a more colourful era.

As depressing as it is that Gen Z is grasping this needily at the bygone eras of fashion and art, it may just reintroduce (if only by accident) the very same elements that made those more expressive than the present one.

Then the other reason: We. Are. Broke.

I’m writing this article in a green-striped long-sleeve dress shirt and baby blue jeans. Both from the 80s, all of it thrifted – like 90% of my dresser. I’m not alone. Inexpensive, diverse and increasingly trendy, preloved and retro fashion is the trend defined not just by accessibility, comfort and colour but by necessity.

Whether it’s the unbearably pink aesthetic of the mid-2000s or the muted brown texture of the 70s, retro fits are the moment.

More than fashion, flea markets and antique stores throng city sheets, recycling bygone aesthetics and recolouring homes that increasingly feel like the aesthetic equivalent of rice porridge.

I’m not saying we’re getting a new renaissance, and it would be a markedly better reflection on us a society if we found a new way forward. In the meantime though, if the retro trend means a renewed era of colour, I’ll be the first to wear a Britney fit.